http://gizmodo.com/a-book-of-tweets-by-people-claiming-theyre-working-on-t-1614304211

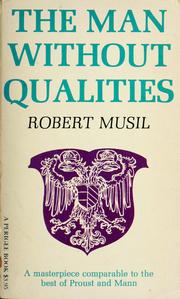

The Man Without Qualities (1930–42; German: Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften) is an unfinished novel in three books by the Austrian writer Robert Musil.

The novel is a “story of ideas”, which takes place in the time of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy’s last days, and the plot often veers into allegorical dissections of a wide range of human themes and feelings.

A condensed history of an innovative moment in publishing history revives the visionary potentials within the humble paperback format. Domus speaks to authors Jeffrey Schnapp and Adam Michaels. A book review from New York by Alan Rapp

http://www.domusweb.it/en/book-review/the-electric-information-age-book/

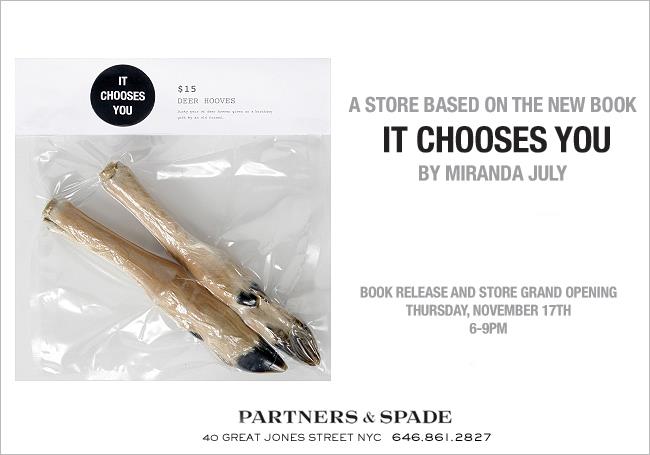

In celebration of “It Chooses You”, Miranda July and her team scoured the New York classifieds, buying up once-meaningful objects and interviewing the sellers. These items, ranging from a modest bottle cap collection to a massive work of art, will be resold for the original asking price (plus tax) at Miranda July’s resale shop within Partners & Spade. Specially-designed packaging will offer insights into the lives behind the hundreds of unique objects, and the local sellers will be in attendance — as will Miranda July herself, signing copies of “It Chooses You”. Joe Putterlik’s obscene and tender homemade cards (described in the book) will also be on display.

A live episode of Design Matters with Debbie Millman was filmed at the School of Visual Arts Masters in Branding Studio by Hillman Curtis late last year to celebrate the launch of Malcolm Gladwell’s illustrated collection of The Tipping Point, Blink and Outliers.

Guests included artist and illustrator Brian Rea, designer Paul Sahre, Josh Liberson, Vice President at One Kings Lane, and DeeDee Gordon, President of Innovation at Sterling Brands. Hear all about the trials and tribulations of this historic collaboration and the trajectory this project took from concept to creation.

http://observermedia.designobserver.com/video/malcolm-gladwell/32388/

Text: http://web.archive.org/web/20060528160418/http://courses.essex.ac.uk/lt/lt204/forking_paths.htm

Wiki: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Garden_of_Forking_Paths

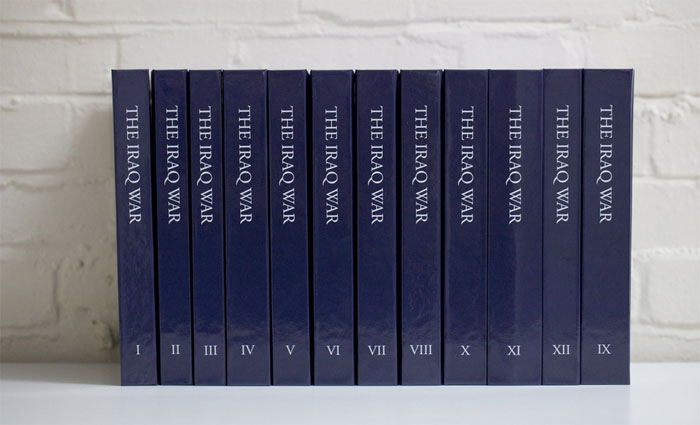

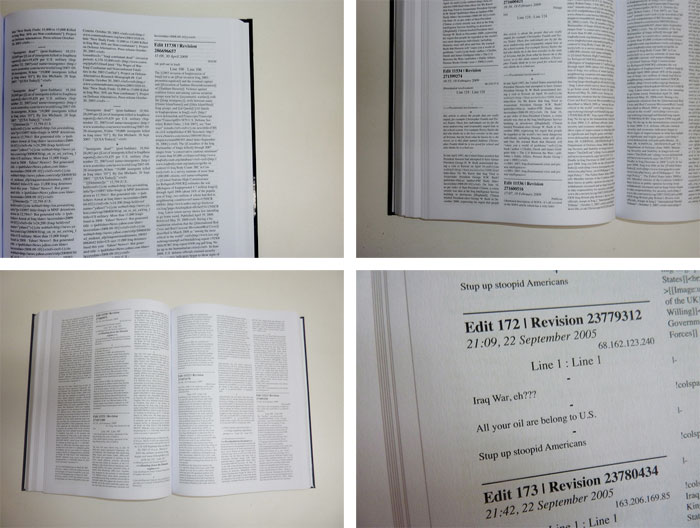

a set of 12 bound volumes documenting every change made to the Wikipedia entry for “the Iraq War” over a period of five years

by James Bridle

There is an increasingly pervasive notion that other forms of media are additive to literature, that they somehow improve it. Because, you know, books are just telling stories, right?

We are witnessing a profound assault on book publishing and literature, on the text itself—not from ebooks, which publishers are slowly, painfully coming around to after a long resistance, or the internet, which is after all entirely made of text—but from applications, “enhanced” books and reductive notions of literary experience. As I’ve written about before, in the context of advertising, publishers’ reactions to new technologies betray a profound lack of confidence in the text itself. We are being distracted by shiny things.

Text lasts. It’s not platform-dependant, you don’t just get it from one source, read it in one place, understand it in one way. It is not dependent on technology: it is what we make technology out of. Code is text, it is the fundamental nature of technology. We’ve been trying for decades, since the advent of hypertext fiction, of media-rich CD-ROMs, to enhance the experience of literature with multimedia. And it has failed, every time.

Yet we are terrified that in the digital age, people are constantly distracted. That they’re shallower, lazier, more dazzled. If they are, then the text is not speaking clearly enough. We are not speaking clearly enough. Like over-stuffed attendees at a dull banquet, the mind wanders. We are terrified that people are dumbing down, and so we provide them with ever dumber entertainment. We sell them ever greater distractions, hoping to dazzle them further.

Literature is an active process: the communication between writer—who wishes to tell the reader something, and imagines that reader in their mind in order to best adapt their writing for their understanding—and reader, who reconstructs and reanimates the text in their own mind. Any other input, audio or video, however pleasurable in certain contexts, diminishes the reader’s capacity for imagination and understanding. All else is distraction. Other—particularly visual—media reduce the bandwidth of the imagination.

“Storytelling” is what we do for children. It is the infantilisation of literature. And while there is much of interest in children’s literature and children’s publishing, to emulate it is to debase literature, and ourselves. (It’s dangerous in science, technology and other non-fiction too: no application or television programme is equal to a well-written, long form text.)

And these reductive notions of literature infect the rest of the body. Contrary to popular thought, everyone is not a publisher. When you hear a publisher say it, it’s even sadder. Publishing is a complex and well established collection of knowledge, competencies and processes, refined over time, practiced under forever difficult circumstances in a frankly indifferent market. Which is not to say that it’s exclusive: the bar to entry has dropped massively, obviously, in the last ten years. But it’s still hard, and hard to do well, and the rewards are still small. Writing something and putting it on the internet is not publishing. Producing an application and getting it into the app store is not publishing. If you think everyone is a publisher, go home now, and come back when you’ve thought about what you do.

In my writing on advertising, I suggested looking to Amazon and Apple as to how to market reading: it’s in the text itself. Amazon in particular are making a killing with the Kindle, they’re eating the publishing business, and they’re doing it by focussing on text. Kindle Singles and related ventures like Byliner and Random House’s Brain Shots take advantage of digital text’s primary advantage: speed. (See the opposing directions of The Guardian’s liveblogs and News International’s The Daily for fundamental understandings and misunderstandings of digital text.)

Added to the velocity of the new text is its sociability, its connectivity. Social reading, whether of the Kindle highlights, Kobo Dashboard, Instapaper, Findings or Readmill flavour, adds depth to the text without diminishing it. When I write about the reading experience, I’m talking about a deep engagement with text, an active, intelligent, two-way conversation between reader and writer.* I am not talking about pretty pictures, sound effects, film clips, or point-and-click “interaction”. 1001 words trump a picture, and books have always been interactive. (There is so much of value in comics, films and games but it is not what book publishers do.)

Finally, the text still requires context. As publishers spin up their digital and print-on-demand backlists, more and more is published with less and less context. These efforts amount to land-grabs and rights-squatting, without adding value. Works without TOCs, indexes, author bios, footnotes. Placing work in context is one of publishers’ primary tasks, stretching out to commissioning introductions, assembling background material, supporting biographies and critical studies. Design belongs here too: good book design, appropriate book design, as important now as it has ever been.

Velocity, depth, breadth. These are the dimensions we can add to books, that are the gifts of a digital age, not gimmicks, glossy presentation and media-catching stunts.

The text works. It stands and speaks for itself. It is not what we need to change.

http://booktwo.org/notebook/the-new-value-of-text/

This book is devided in two parts. The first one is the Chinese government state TV censorship keywords list, found in a wikileaks article. The second one try to give an explanation or / and a face to those words.

In addition to the individual fictions, which are more or less protected from tampering in the old proprietary way, we in the workshop have also played freely and often quite anarchically in a group fiction space called “Hotel.” Here, writers are free to check in, to open up new rooms, new corridors, new intrigues, to unlink texts or create new links, to intrude upon or subvert the texts of others, to alter plot trajectories, manipulate time and space, to engage in dialogue through invented characters, then kill off one another’s characters or even to sabotage the hotel’s plumbing. Thus one day we might find a man and woman encountering each other in the hotel bar, working up some kind of sexual liaison, only to return a few days later and discover that one or both had sex changes. During one of my hypertext workshops, a certain reading tension was caused when we found that there was more than one bartender in our hotel: was this the same bar or not? One of the students — Alvin Lu again — responded by linking all the bartenders to Room 666, which he called the “Production Center,” where some imprisoned alien monster was giving birth to full-grown bartenders on demand.

————————————————————————————-

Welcome

to the recently renovated Hypertext Hotel. All newly elected members of the BOARD OF DIRECTORS may read, write, and sleep over here, moving in wherever they feel most comfortable, the whole Hotel at their disposal. Guests, too, may range freely. This is not so much a friendly hotel as it is one without proper management, which is to say that within its rooms and corridors, virtually anything can happen…

All visitors who have left behind some evidence of their stopover are invited to sign The Guestbook. The Management would like to thank the Friends of the Hotel for their generous contributions.

Please pick up the Housephone.

http://netlern.net/hyperdis/hyphotel/

via http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/09/27/specials/coover-end.html

In the real world nowadays, that is to say, in the world of video transmissions, cellular phones, fax machines, computer networks, and in particular out in the humming digitalized precincts of avant-garde computer hackers, cyberpunks and hyperspace freaks, you will often hear it said that the print medium is a doomed and outdated technology, a mere curiosity of bygone days destined soon to be consigned forever to those dusty unattended museums we now call libraries. Indeed, the very proliferation of books and other print-based media, so prevalent in this forest-harvesting, paper-wasting age, is held to be a sign of its feverish moribundity, the last futile gasp of a once vital form before it finally passes away forever, dead as God.

Which would mean of course that the novel, too, as we know it, has come to its end. Not that those announcing its demise are grieving. For all its passing charm, the traditional novel, which took center stage at the same time that industrial mercantile democracies arose — and which Hegel called “the epic of the middle-class world” — is perceived by its would-be executioners as the virulent carrier of the patriarchal, colonial, canonical, proprietary, hierarchical and authoritarian values of a past that is no longer with us.

Much of the novel’s alleged power is embedded in the line, that compulsory author-directed movement from the beginning of a sentence to its period, from the top of the page to the bottom, from the first page to the last. Of course, through print’s long history, there have been countless strategies to counter the line’s power, from marginalia and footnotes to the creative innovations of novelists like Laurence Sterne, James Joyce, Raymond Queneau, Julio Cortazar, Italo Calvino and Milorad Pavic, not to exclude the form’s father, Cervantes himself. But true freedom from the tyranny of the line is perceived as only really possible now at last with the advent of hypertext, written and read on the computer, where the line in fact does not exist unless one invents and implants it in the text.

“Hypertext” is not a system but a generic term, coined a quarter of a century ago by a computer populist named Ted Nelson to describe the writing done in the nonlinear or nonsequential space made possible by the computer. Moreover, unlike print text, hypertext provides multiple paths between text segments, now often called “lexias” in a borrowing from the pre-hypertextual but prescient Roland Barthes. With its webs of linked lexias, its networks of alternate routes (as opposed to print’s fixed unidirectional page-turning) hypertext presents a radically divergent technology, interactive and polyvocal, favoring a plurality of discourses over definitive utterance and freeing the reader from domination by the author. Hypertext reader and writer are said to become co-learners or co-writers, as it were, fellow-travelers in the mapping and remapping of textual (and visual, kinetic and aural) components, not all of which are provided by what used to be called the author.

Though used at first primarily as a radically new teaching arena, by the mid-1980’s hyperspace was drawing fiction writers into its intricate and infinitely expandable, infinitely alluring webs, its green-limned gardens of multiple forking paths, to allude to another author popular with hypertext buffs, Jorge Luis Borges.

Several systems support the configuring of this space for fiction writing. Some use simple randomized linking like the shuffling of cards, others (such as Guide and HyperCard) offer a kind of do-it-yourself basic tool set, and still others (more elaborate systems like Storyspace, which is currently the software of choice among fiction writers in this country, and Intermedia, developed at Brown University) provide a complete package of sophisticated structuring and navigational devices.

Although hypertext’s champions often assail the arrogance of the novel, their own claims are hardly modest. You will often hear them proclaim, quite seriously, that there have been three great events in the history of literacy: the invention of writing, the invention of movable type and the invention of hypertext. As hyperspace-walker George P. Landow puts it in his recent book surveying the field, “Hypertext”: “Electronic text processing marks the next major shift in information technology after the development of the printed book. It promises (or threatens) to produce effects on our culture, particularly on our literature, education, criticism and scholarship, just as radical as those produced by Gutenberg’s movable type.”

Noting that the “movement from the tactile to the digital is the primary fact about the contemporary world,” Mr. Landow observes that, whereas most writings of print-bound critics working in an exhausted technology are “models of scholarly solemnity, records of disillusionment and brave sacrifice of humanistic positions,” writers in and on hypertext “are downright celebratory. . . . Most poststructuralists write from within the twilight of a wished-for coming day; most writers of hypertext write of many of the same things from within the dawn.”

Dawn it is, to be sure. The granddaddy of full-length hypertext fictions is Michael Joyce’s landmark “Afternoon,” first released on floppy disk in 1987 and moved into a new Storyspace “reader,” partly developed by Mr. Joyce himself, in 1990.

Mr. Joyce, who is also the author of a printed novel, “The War Outside Ireland: A History of the Doyles in North America With an Account of their Migrations,” wrote in the on-line journal Postmodern Culture that hyperfiction “is the first instance of the true electronic text, what we will come to conceive as the natural form of multimodal, multisensual writing,” but it is still so radically new it is hard to be certain just what it is. No fixed center, for starters — and no edges either, no ends or boundaries. The traditional narrative time line vanishes into a geographical landscape or exitless maze, with beginnings, middles and ends being no longer part of the immediate display. Instead: branching options, menus, link markers and mapped networks. There are no hierarchies in these topless (and bottomless) networks, as paragraphs, chapters and other conventional text divisions are replaced by evenly empowered and equally ephemeral window-sized blocks of text and graphics — soon to be supplemented with sound, animation and film.

As Carolyn Guyer and Martha Petry put it in the opening “directions” to their hypertext fiction “Izme Pass,” which was published (if “published” is the word) on a disk included in the spring 1991 issue of the magazine Writing on the Edge:

“This is a new kind of fiction, and a new kind of reading. The form of the text is rhythmic, looping on itself in patterns and layers that gradually accrete meaning, just as the passage of time and events does in one’s lifetime. Trying the textlinks embedded within the work will bring the narrative together in new configurations, fluid constellations formed by the path of your interest. The difference between reading hyperfiction and reading traditional printed fiction may be the difference between sailing the islands and standing on the dock watching the sea. One is not necessarily better than the other.”

I must confess at this point that I am not myself an expert navigator of hyperspace, nor am I — as I am entering my seventh decade and thus rather committed, for better or for worse, to the obsolescent print technology — likely to engage in any major hypertext fictions of my own. But, interested as ever in the subversion of the traditional bourgeois novel and in fictions that challenge linearity, I felt that something was happening out (or in) there and that I ought to know what it was: if I were not going to sail the Guyer-Petry islands, I had at least better run to the shore with my field glasses. And what better way to learn than to teach a course in the subject?

Thus began the Brown University Hypertext Fiction Workshop, two spring semesters (and already as many software generations) old, a course devoted as much to the changing of reading habits as to the creation of new narratives.

Writing students are notoriously conservative creatures. They write stubbornly and hopefully within the tradition of what they have read. Getting them to try out alternative or innovative forms is harder than talking them into chastity as a life style. But confronted with hyperspace, they have no choice: all the comforting structures have been erased. It’s improvise or go home. Some frantically rebuild those old structures, some just get lost and drift out of sight, most leap in fearlessly without even asking how deep it is ( infinitely deep) and admit, even as they paddle for dear life, that this new arena is indeed an exciting, provocative if frequently frustrating medium for the creation of new narratives, a potentially revolutionary space, capable, exactly as advertised, of transforming the very art of fiction, even if it now remains somewhat at the fringe, remote still, in these very early days, from the mainstream.

With hypertext we focus, both as writers and as readers, on structure as much as on prose, for we are made aware suddenly of the shapes of narratives that are often hidden in print stories. The most radical new element that comes to the fore in hypertext is the system of multidirectional and often labyrinthine linkages we are invited or obliged to create. Indeed the creative imagination often becomes more preoccupied with linkage, routing and mapping than with statement or style, or with what we would call character or plot (two traditional narrative elements that are decidedly in jeopardy). We are always astonished to discover how much of the reading and writing experience occurs in the interstices and trajectories between text fragments. That is to say, the text fragments are like stepping stones, there for our safety, but the real current of the narratives runs between them.

“The great thing,” as one young writer, Alvin Lu, put it in an on-line class essay, is “the degree to which narrative is completely destructed into its constituent bits. Bits of information convey knowledge, but the juxtaposition of bits creates narrative. The emphasis of a hypertext (narrative) should be the degree to which the reader is given power, not to read, but to organize the texts made available to her. Anyone can read, but not everyone has sophisticated methods of organization made available to them.”

The fictions developed in the workshop, all of which are “still in progress,” have ranged from geographically anchored narratives similar to “Our Town” and choose-your-own-adventure stories to parodies of the classics, nested narratives, spatial poems, interactive comedy, metamorphic dreams, irresolvable murder mysteries, moving comic books and Chinese sex manuals.

IN hypertext, multivocalism is popular, graphic elements, both drawn and scanned, have been incorporated into the narratives, imaginative font changes have been employed to identify various voices or plot elements, and there has also been a very effective use of formal documents not typically used in fictions — statistical charts, song lyrics, newspaper articles, film scripts, doodles and photographs, baseball cards and box scores, dictionary entries, rock music album covers, astrological forecasts, board games and medical and police reports.

At our weekly workshops, selected writers display, on an overhead projector, their developing narrative structures, then face the usual critique of their writing, design, development of character, emotional impact, attention to detail and so on, as appropriate. But they also engage in continuous on-line dialogue with one another, exchanging criticism, enthusiasm, doubts, speculations, theorizing, wisecracks. So much fun is all of this, so compelling this “downright celebratory” experience, as Mr. Landow would have it, that the creative output, so far anyway, has been much greater than that of ordinary undergraduate writing workshops, and certainly of as high a quality.

In addition to the individual fictions, which are more or less protected from tampering in the old proprietary way, we in the workshop have also played freely and often quite anarchically in a group fiction space called “Hotel.” Here, writers are free to check in, to open up new rooms, new corridors, new intrigues, to unlink texts or create new links, to intrude upon or subvert the texts of others, to alter plot trajectories, manipulate time and space, to engage in dialogue through invented characters, then kill off one another’s characters or even to sabotage the hotel’s plumbing. Thus one day we might find a man and woman encountering each other in the hotel bar, working up some kind of sexual liaison, only to return a few days later and discover that one or both had sex changes. During one of my hypertext workshops, a certain reading tension was caused when we found that there was more than one bartender in our hotel: was this the same bar or not? One of the students — Alvin Lu again — responded by linking all the bartenders to Room 666, which he called the “Production Center,” where some imprisoned alien monster was giving birth to full-grown bartenders on demand.

This space of essentially anonymous text fragments remains on line and each new set of workshop students is invited to check in there and continue the story of the Hypertext Hotel. I would like to see it stay open for a century or two.

However, as all of us have discovered, even though the basic technology of hypertext may be with us for centuries to come, perhaps even as long as the technology of the book, its hardware and software seem to be fragile and short-lived; whole new generations of equipment and programs arrive before we can finish reading the instructions of the old. Even as I write, Brown University’s highly sophisticated Intermedia system, on which we have been writing our hypertext fictions, is being phased out because it is too expensive to maintain and incompatible with Apple’s new operating-system software, System 7.0. A good portion of our last semester was spent transporting our documents from Intermedia to Storyspace (which Brown is now adopting) and adjusting to the new environment.

This problem of operating-system standards is being urgently addressed and debated now by hypertext writers; if interaction is to be a hallmark of the new technology, all its players must have a common and consistent language and all must be equally empowered in its use. There are other problems too. Navigational procedures: how do you move around in infinity without getting lost? The structuring of the space can be so compelling and confusing as to utterly absorb and neutralize the narrator and to exhaust the reader. And there is the related problem of filtering. With an unstable text that can be intruded upon by other author-readers, how do you, caught in the maze, avoid the trivial? How do you duck the garbage? Venerable novelistic values like unity, integrity, coherence, vision, voice seem to be in danger. Eloquence is being redefined. “Text” has lost its canonical certainty. How does one judge, analyze, write about a work that never reads the same way twice?

And what of narrative flow? There is still movement, but in hyperspace’s dimensionless infinity, it is more like endless expansion ; it runs the risk of being so distended and slackly driven as to lose its centripetal force, to give way to a kind of static low-charged lyricism — that dreamy gravityless lost-in-space feeling of the early sci-fi films. How does one resolve the conflict between the reader’s desire for coherence and closure and the text’s desire for continuance, its fear of death? Indeed, what is closure in such an environment? If everything is middle, how do you know when you are done, either as reader or writer? If the author is free to take a story anywhere at any time and in as many directions as she or he wishes, does that not become the obligation to do so?

No doubt, this will be a major theme for narrative artists of the future, even those locked into the old print technologies. And that’s nothing new. The problem of closure was a major theme — was it not? — of the “Epic of Gilgamesh” as it was chopped out in clay at the dawn of literacy, and of the Homeric rhapsodies as they were committed to papyrus by technologically innovative Greek literati some 26 centuries ago. There is continuity, after all, across the ages riven by shifting technologies.

Much of this I might have guessed — and in fact did guess — before entering hyperspace, before I ever picked up a mouse, and my thoughts have been tempered only slightly by on-line experience. What I had not clearly foreseen, however, was that this is a technology that both absorbs and totally displaces. Print documents may be read in hyperspace, but hypertext does not translate into print. It is not like film, which is really just the dead end of linear narrative, just as 12-tone music is the dead end of music by the stave.

Hypertext is truly a new and unique environment. Artists who work there must be read there. And they will probably be judged there as well: criticism, like fiction, is moving off the page and on line, and it is itself susceptible to continuous changes of mind and text. Fluidity, contingency, indeterminacy, plurality, discontinuity are the hypertext buzzwords of the day, and they seem to be fast becoming principles, in the same way that relativity not so long ago displaced the falling apple.

Like most companies, Google regularly communicates with our business customers via email newsletters, updates on our official blogs, and printed materials.

On this occasion, we’ve sent a short book about data, called Think Quarterly, to a small number of our UK partners and advertisers. You’re now on the companion website, thinkquarterly.co.uk (also available at m.thinkquarterly.co.uk, if you’re on the move).We’re flattered by the positive reaction but have no plans to start selling copies! Although Think Quarterly remains firmly aimed at Google’s partners and advertisers, if you’re interested in the subject of data then please feel free to read on…http://thinkquarterly.co.uk/

DIASPAR is forty-five reactions to randomness generated by internationally recognised experts from dozens of different fields. These articles overlap each other in complex ways, drawing lines of connection that crosshatch into a map which must be navigated as a labyrinth. It slowly explains itself as you travel through it, but there is no end (or beginning).

http://earstone.com/indexhibit/index.php?/projects/graphics-images-chinese/

After ten days of travelling China, I designed an image book of personal impression on Chinese graphic design. The Chinese designers I met had a great love for their traditions, but at the same time seemed to be under the pressure to break out of the traditions. Long explanations were excluded in my work. Rather, I tried to communicate only with images and a few words. This book is on sale at an independent publisher book store in Seoul.

2009, 150×220mm, 56pages, Offset print. Book

2009, 590×850mm, Digital print. Poster

I AM YOU, a book by Ellen Zhao, talks about the relationship between the book and the reader. While documenting its own process from conception to realization, the book contemplates about the identity of the reader.

Limited edition of 500.

Collected by the the New York Public Library Artist Books, Getty Artist books, Cabinet du livre d’artiste, galerie immanence, and the bnf.

I AM YOU is sold at Printed Matter in New York, Librairie Galerie Anatome and Librairie Yvonne Lambert in Paris, and nijhof and lee in Amsterdam.

Or you can write directly here to acquire your own copy. $25 or 20 euros, plus shipping and handling.

More at:

Balla Dora, Changethethought, Etienne Mineur Archives, FFFFound, Rag and Bones, The Magenta Links, Manystuff

http://www.buro-gds.com/08-redaxo/index.php?article_id=46&clang=0

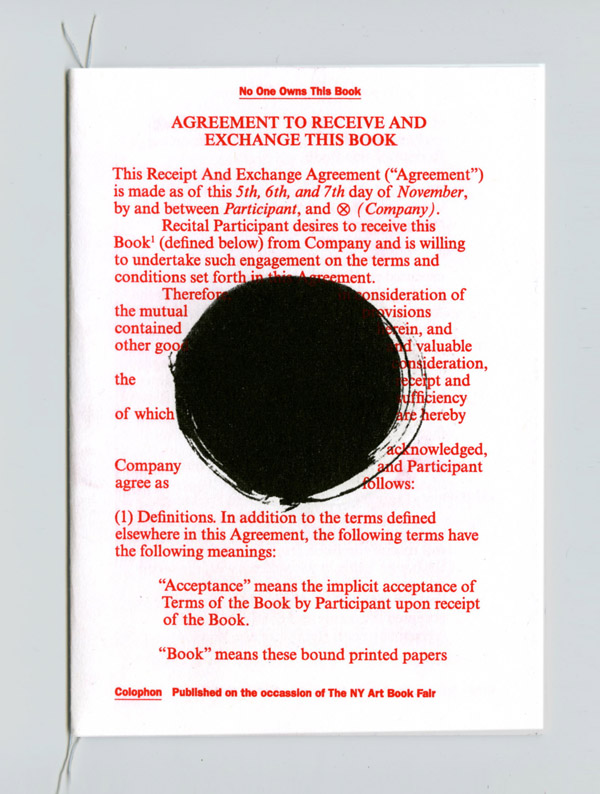

Investment Futures Strategy, Ltd. is pleased to announce The Book Trust, a site specific collaboration and publication to be presented at the NY Art Book Fair, 5-7 November, 2010. The semi-fictional IFS, Ltd., comprised of five graduate students from the Department of Graphic Design at the Yale University School of Art, will offer an original publication for trade in a series of barters executed by its authors during the three days of the Fair.

The Trust and the accompanying Book Trust Prospectus speak to matters of micro-economies and distribution, as well as prescribed and perceived value. The project suggests a new currency specific to the setting of the Book Fair, a context in which a distinct set of commodities is exchanged by like-minded vendors in a finite space and time. It is only in this setting that a book could be posited as capital—a literal stand-in for the money that commonly exchanges hands at the Fair. Perceived worth is no longer dictated by edition or price, but instead by a potential traders’ subjective notion of the values they assign to each book.

The book, produced in a fixed quantity of 500, will vary in value as each negotiation determines and redetermines its worth in the marketplace. With each transaction, the Prospectus will assume the value of the book for which it was exchanged. The traded commodities will ultimately comprise The Book Trust, a value-appreciating book bank. By trading with IFS, Ltd. participants acquire a single theoretical share of the bank, the Prospectus a document of the transaction.

At the close of the trading day, 5PM on 7 November, IFS, Ltd. will assess and catalogue the contents of the Trust with the intention of circulating its holdings in appropriate domestic and international venues, at which point new editions of the Prospectus may be issued in context-specific reenactments of the initial trading period.

In framing the project in a format similar to that of a stock exchange, the performance emphasizes the tenuous and abstract value of the book as a designed object, as a medium for content, as a traded commodity, and as a symbol of participation in the project itself.

At the 2010 New York Art Book Fair multiple exhibitors proposed that books can be a type of currency, and would only exchange their book or their goods for another book. As a form of intervention we proposed a loop-hole currency — a book meant only for trading. Using guerrilla strategies, my collaborator Keri Bronk and I sat on the PS1 steps and distributed our book for free explaining it was a type of voucher that could be traded for another book inside.

The black spot alludes to Treasure island, where a page of the bible is delivered with a large black mark indicating future misfortune. In the case of our book we reversed this and suggested the spot as a predictive mark— a foreshadowing of good fortune in the form of a new book.

http://www.ryanweafer.com/#765534/Agreement-to-Receive-Exchange-This-Book

A NEW method developed by Marcus Gärde to produce gridsystems based on old books and scrolls.During his research when writing his first book, The Way of Typography, Garde found out that old bibles and scrolls where not designed in the same manner as todays books – they where actually more complex!

In fact, the baselinegrid always fitted perfectly on the page. And even the gutter was in proportion to the lead. For exampel, in Gutenbergs B36 the gutter is 1/3 of the outer margin. The inner margin is 1/2 of the outer. The upper margin is 1/2 of the lower. The typographic area contains 6 modules and each of these modules are divided 6 times. That creates the 36 lines of text. In Gutenbergs first book, B42, the 6 modules where each divided 7 times. Therefore 42 lines of text.

After Marcus had examined the books, he created a step-to-step guide howe to create a perfect gridsystem,

where all the baselines fit inside the page and the gutter is based on the proportion of the lead.

He released this method in his book The Way of Typography august 2007.

edit: I realized that this is great if you have absolute control over the production, but if your printer doesn’t do full-bleed perfectly, you’re wasting a lot of time.

A book is a sequence of spaces.

Each of these spaces is perceived at a different moment - a book is also a sequence of moments.

A book is not a case of words, nor a bag of words, nor a bearer of words.

Looking for a dystopian notion for your sci-fi novel? Look no further. Mayer-Schönberger warns about the social and political costs and risks of ever-powerful, durable forms of memory prosthetics in the form of digital technologies, and proposes solutions.

http://www.amazon.com/exec/obidos/ASIN/0691138613/designobserver-20/

Sarah Cook and Beryl Graham, co-editors of the CRUMB site and list (the Curatorial Resource for Upstart Media Bliss), have co-authored the book via email and on a Wiki, and assert outright that it is not a “theory book”; its structure instead “reflects the CRUMB approach to research, which discusses and analyzes the process of how things are done” (12). The sheer number of examples, citations, and first-person accounts in this nearly 350-page volume make it so that every time the trajectory coheres into a singular point or argument, it is then broken up again, into a constellation of ideas that make us rethink, again. We are issued challenge after challenge to our assumptions about media, our understandings of curatorial practice, and our opinions about the spaces in which we exhibit art. It is only after an exhaustive study of seemingly irreconcilable philosophies, practices and venues, the book implicitly argues, that we can begin to engage with what needs to be rethought, and how to do so.

Rethinking Curating makes three basic arguments. First, that one must approach a broad set of histories in trying to understand any given artwork, and “for new media art this set includes technological histories, which are essentially interdisciplinary and patchily documented” (283). Second, that such broad histories have led to the unique development of “critical vocabularies for the fluid and overlapping characteristics of new media art” (283). Cook and Graham reason that new media are best understood not as materials but as “behaviors” – participatory, performative or generative, for example. And third, that these behaviors demand a rethinking of curating, new modes of “looking at the production, exhibition, interpretation, and wider dissemination (including collection and conservation) of new media art” (1).