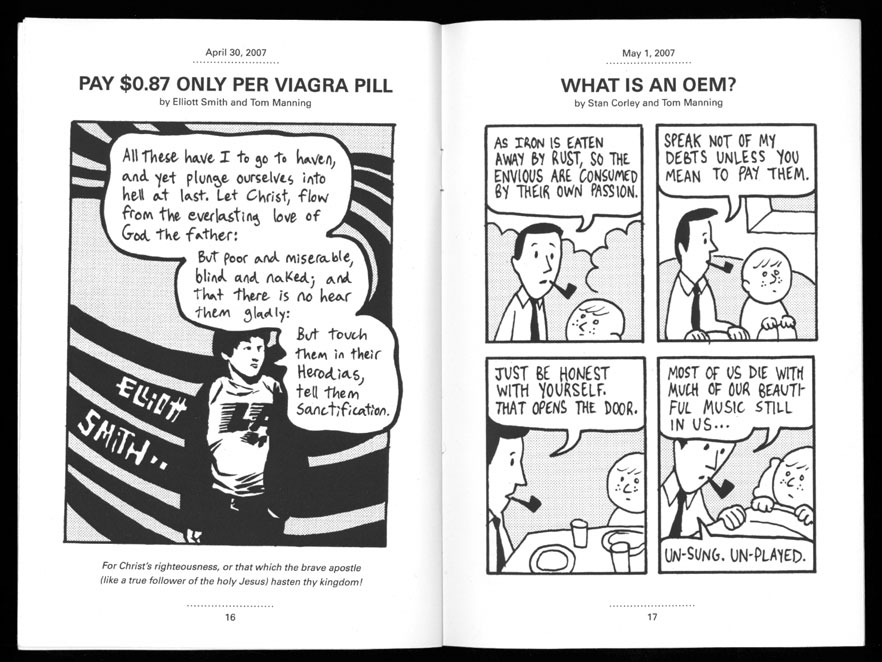

28 page book transforming spam into daily comic strips 2007

SPAM COLLABORATIONS

The Highlights

The Highlights began as a response to the journalistic bent in art reviews, offering artists an outlet to engage in uncon– ventional criticism. Since that time, we have enlarged the format to include experimental text and digital media projects. These works are an extension of the artists’ own practice and consist of image-based essays, original videos, interviews, as well as fictional, virtual, biographic, and diaristic writing. All completed projects are stored permanently in the online archive where they are available for browsing.

Google’s new online magazine: Think Quarterly

Like most companies, Google regularly communicates with our business customers via email newsletters, updates on our official blogs, and printed materials.

On this occasion, we’ve sent a short book about data, called Think Quarterly, to a small number of our UK partners and advertisers. You’re now on the companion website, thinkquarterly.co.uk (also available at m.thinkquarterly.co.uk, if you’re on the move).We’re flattered by the positive reaction but have no plans to start selling copies! Although Think Quarterly remains firmly aimed at Google’s partners and advertisers, if you’re interested in the subject of data then please feel free to read on…http://thinkquarterly.co.uk/

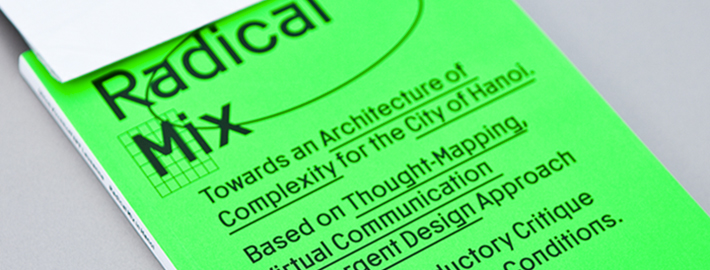

Behind The Zines

Social networks are dominating today‘s headlines, but they are not the only platforms that are radically changing the way we communicate. Creatives such as designers, photographers, artists, researchers, and poets are disseminating information about themselves and their favorite subjects not via predefined media such as Twitter or blogs, but through printed or other self-published projects—so-called zines. Those who publish zines are mostly interested in sole authorship, namely that all components including text, images, layout, typography, production, and distribution are firmly in the hands of one person or a small group. At their best, the results convey a compelling and consistent atmosphere and push against the established creative grain in just the right way. They provoke with surprising and non-linear food for thought. In short, zines are advancing the evolution of today‘s media.

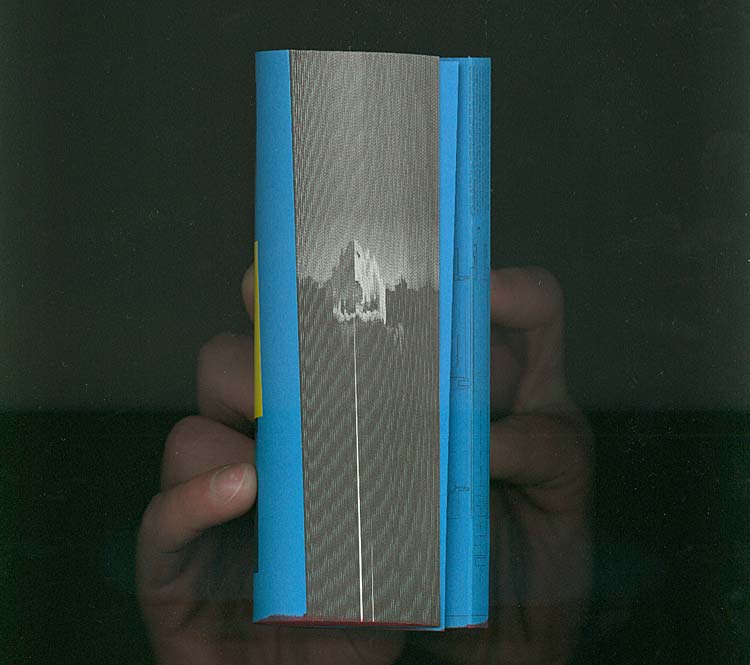

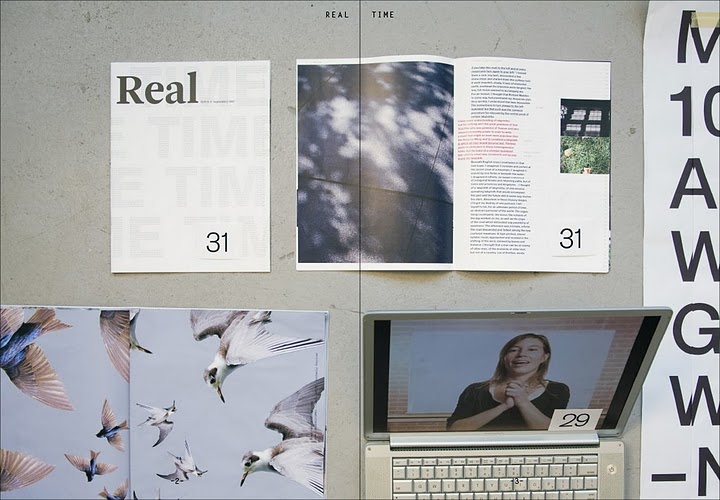

With a cutting-edge selection of international examples, Behind the Zines introduces the broad range of zines that exists today. These include zines that function as a new kind of project-oriented portfolio to showcase a self-profile or document an exhibit. While some act as (pseudo) scientific treatises to call the reader‘s attention to a specific topic, others serve as playrooms for creatives to run riot and express themselves and communicate with each other in a space that is free from editorial restrictions.

The book examines the key factors that distinguish various zines. It introduces projects in which the printing process significantly influences aesthetics or in which limited distribution to a small, clearly defined target audience becomes part of the overall concept.

Behind the Zines not only documents outstanding work, but also shows how the self-image of those who make zines impacts the scene as a whole. Through interviews with people involved in zine production and distribution, the book sheds light on various strategies for this evolving media form.

via Manystuff.

Manifesto

MTV______ME by WOOG

Elektrotechnique

Elektrotechnique from Lernert & Sander on Vimeo.

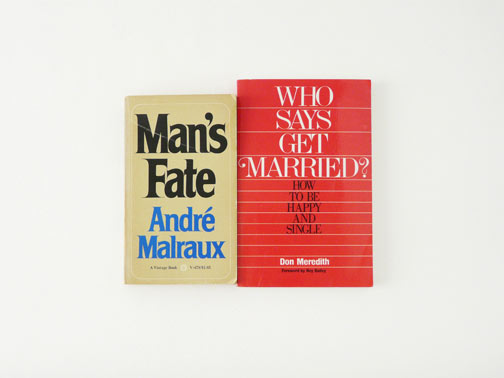

Covered

Dan Scanlon covers X-Men 1

http://coveredblog.blogspot.com/

http://coveredblog.blogspot.com/2009/11/dan-scanlon-covers-x-men-1.html

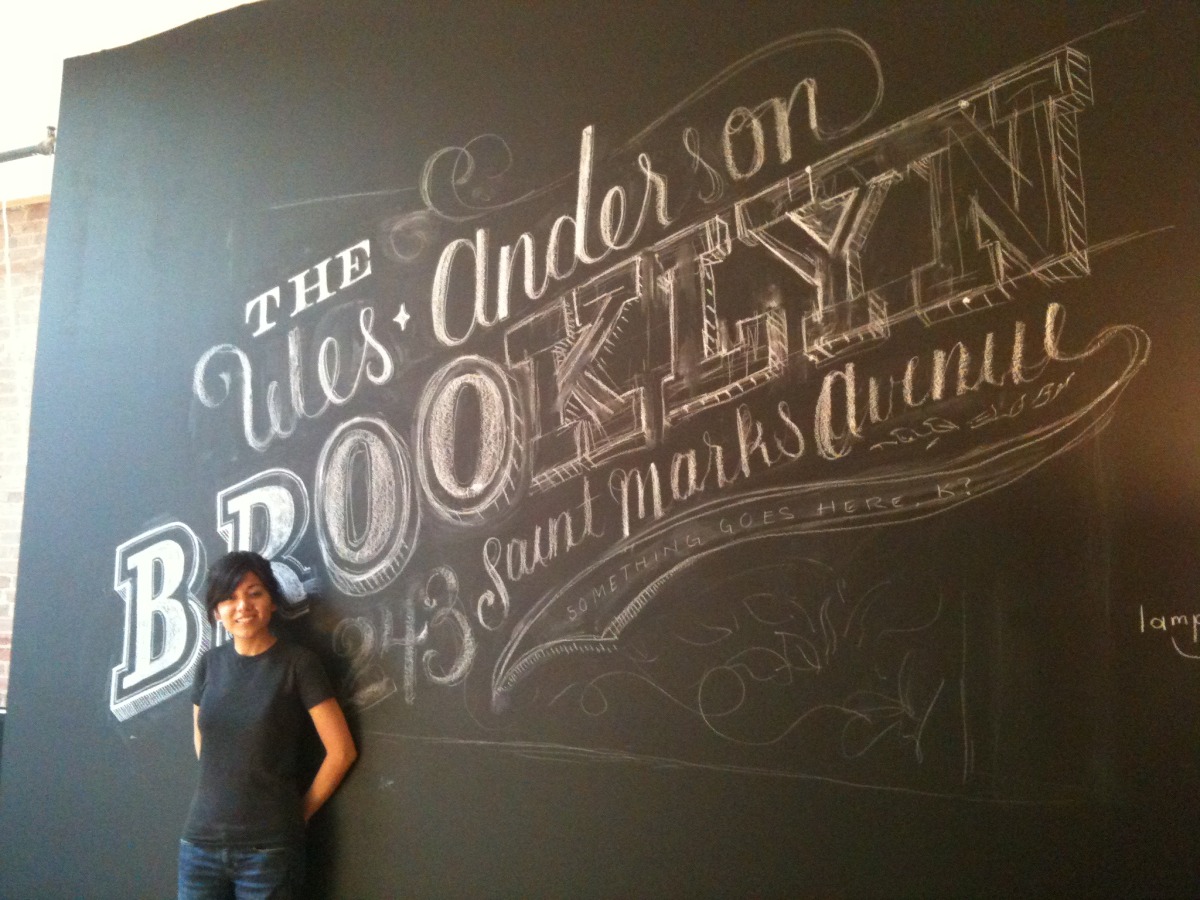

Dan Tanamachi

Dana Tanamachi is a graphic designer and custom chalk letterer living in Brooklyn, New York.She currently works at Louise Fili Ltd.

Sexy Machinery

Magazine by Abake

http://www.sexymachinery.com/

Elegant Dissent: Elliott Earls talk at the ICA Boston

Cult Youth

CULT YOUTH from Diesel New Voices on Vimeo.

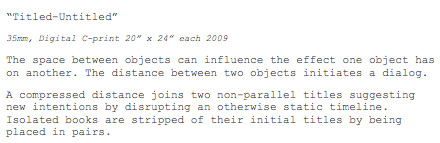

collected-recollected

https://picasaweb.google.com/daniellaspinat/CollectedRecollected?authkey=Gv1sRgCOP8psza5fXPUQ&feat=embedwebsite#

https://picasaweb.google.com/daniellaspinat/CollectedRecollected?authkey=Gv1sRgCOP8psza5fXPUQ&feat=embedwebsite#

Five Years of 100 Days

Daniella Spinat and Lan Lan Liu, Announcement for 100 Day Project Workshop, 2007For the past five years, I’ve taught a workshop for the graduate graphic design students at the Yale School of Art. The specific dates always change, but the basic assignment goes something like this:Beginning Thursday, October 21, 2010, do a design operation that you are capable of repeating every day. Do it every day between today and up to and including Friday, January 28, 2011, the last day of the project, by which time you will have done the operation one hundred times. That afternoon, each student will have up to 15 minutes to present his or her one-hundred part project to the class.The only restrictions on the operation you choose is that it must be repeated in some form every day, and that every iteration must be documented for eventual presentation. The medium is open, as is the final form of the presentation on the 100th day.Does this sound like fun? I’m not sure. But some years, up to two dozen students start the assignment. And some years, more than half drop out before the end. Everyone starts with high hopes. But things get repetitive by day ten. By day twenty, no matter what you’ve decided to do, it feels like you’ve been doing it forever. And bridging the end-of-year break is always a big challenge. But the students who get past day thirty or forty tend to get in a groove that will take them through to the end. Here’s a sampling of what’s been done through the years, including some of my favorites.Lauren Adolfsen took a picture each day with a person she had never met. The product was a bound book, complete with thumbnail sketches of her portrait partners. I was number one. Amazingly, she ended up doing this for an entire year.

Daniella Spinat and Lan Lan Liu, Announcement for 100 Day Project Workshop, 2007For the past five years, I’ve taught a workshop for the graduate graphic design students at the Yale School of Art. The specific dates always change, but the basic assignment goes something like this:Beginning Thursday, October 21, 2010, do a design operation that you are capable of repeating every day. Do it every day between today and up to and including Friday, January 28, 2011, the last day of the project, by which time you will have done the operation one hundred times. That afternoon, each student will have up to 15 minutes to present his or her one-hundred part project to the class.The only restrictions on the operation you choose is that it must be repeated in some form every day, and that every iteration must be documented for eventual presentation. The medium is open, as is the final form of the presentation on the 100th day.Does this sound like fun? I’m not sure. But some years, up to two dozen students start the assignment. And some years, more than half drop out before the end. Everyone starts with high hopes. But things get repetitive by day ten. By day twenty, no matter what you’ve decided to do, it feels like you’ve been doing it forever. And bridging the end-of-year break is always a big challenge. But the students who get past day thirty or forty tend to get in a groove that will take them through to the end. Here’s a sampling of what’s been done through the years, including some of my favorites.Lauren Adolfsen took a picture each day with a person she had never met. The product was a bound book, complete with thumbnail sketches of her portrait partners. I was number one. Amazingly, she ended up doing this for an entire year. Juan Astasio photographed a constructed “smile” every day. The website where they’re all collected is maniacally over-the-top and terrifyingly cheerful.

Juan Astasio photographed a constructed “smile” every day. The website where they’re all collected is maniacally over-the-top and terrifyingly cheerful. Here’s one you may already know since it was featured on Design Observer back in the fall of 2009: Rachel Berger explains: “Every day for one hundred days (from October 30, 2008 to February 6, 2009) I picked a paint chip out of a bag and responded to it with a short writing.” It sounds simple, but the results are poetic.

Here’s one you may already know since it was featured on Design Observer back in the fall of 2009: Rachel Berger explains: “Every day for one hundred days (from October 30, 2008 to February 6, 2009) I picked a paint chip out of a bag and responded to it with a short writing.” It sounds simple, but the results are poetic. A few people have realized the project could be a modest source of income. Every day, Benjamin Critton found something laying around that he didn’t want and put it up for sale on line, from a copy of the 1963 book The World in Vogue (Day One, offered at $31, unsold) to a box of (appropriately) one hundred numbered pushpins (Day One Hundred, offered at $18, sold).

A few people have realized the project could be a modest source of income. Every day, Benjamin Critton found something laying around that he didn’t want and put it up for sale on line, from a copy of the 1963 book The World in Vogue (Day One, offered at $31, unsold) to a box of (appropriately) one hundred numbered pushpins (Day One Hundred, offered at $18, sold). I have always loved it when people get deep into extremely specific subject matter. Neil Donnelly created a daily visual response to the same song: Brian Eno’s 1974 recording “Here Come the Warm Jets.” The variety is remarkable.

I have always loved it when people get deep into extremely specific subject matter. Neil Donnelly created a daily visual response to the same song: Brian Eno’s 1974 recording “Here Come the Warm Jets.” The variety is remarkable. Weiyi Li spotted a random name every day and added it to an ongoing collection, memorialized in a slowly scrolling website.

Weiyi Li spotted a random name every day and added it to an ongoing collection, memorialized in a slowly scrolling website. “100 Illusions” by Jen Lee.

“100 Illusions” by Jen Lee. After you’ve seen the first few ways that Hilla Katki uses a wooden folding chair, you’ll have serious doubts she can come up with ten of them, never mind 100. But, of course, she does. And it’s a clunky wooden folding chair.

After you’ve seen the first few ways that Hilla Katki uses a wooden folding chair, you’ll have serious doubts she can come up with ten of them, never mind 100. But, of course, she does. And it’s a clunky wooden folding chair. Die a hundred deaths! Tara Kelton destroyed a small plastic man every day a different way for one hundred days.

Die a hundred deaths! Tara Kelton destroyed a small plastic man every day a different way for one hundred days. The most famous graduate of the 100 Day Workshop is, without a doubt, Ely Kim. When I asked him what he had planned, he responded, “I’m going to film myself doing a different dance in a different place every day.” He said it with such absolute assurance that I was taken aback. “Are you a good dancer?” I asked. Ely said: “Yes.” The resulting video, “Boombox,” has been viewed over half a million times and won Ely invitations to dance in, among other places, Sao Paulo, Brazil.

The most famous graduate of the 100 Day Workshop is, without a doubt, Ely Kim. When I asked him what he had planned, he responded, “I’m going to film myself doing a different dance in a different place every day.” He said it with such absolute assurance that I was taken aback. “Are you a good dancer?” I asked. Ely said: “Yes.” The resulting video, “Boombox,” has been viewed over half a million times and won Ely invitations to dance in, among other places, Sao Paulo, Brazil. Zak Klauck: “Over the course of 100 days, I made a poster each day in one minute. The posters were based on one word or short phrase collected from 100 different people. Anyone and everyone was invited to contribute.” The perfect exercise for a graphic designer.

Zak Klauck: “Over the course of 100 days, I made a poster each day in one minute. The posters were based on one word or short phrase collected from 100 different people. Anyone and everyone was invited to contribute.” The perfect exercise for a graphic designer. Although many of these projects are complicated, some of my favorites are completely straightforward. James Muspratt simply drew something from life every day: a project that grew, he writers, “out of a desire to confront my limited drawing skills.”

Although many of these projects are complicated, some of my favorites are completely straightforward. James Muspratt simply drew something from life every day: a project that grew, he writers, “out of a desire to confront my limited drawing skills.” Jieun Rim kept a video camera trained on her feet every day while she walked to school, and edited the 100 separate trips into a single elegant sequence titled “Steppin’ Out.”

Jieun Rim kept a video camera trained on her feet every day while she walked to school, and edited the 100 separate trips into a single elegant sequence titled “Steppin’ Out.” Finally, when Jessica Svendsen told me she wanted to create 100 variations of Josef Muller-Brockmann’s classic 1955 poster for a Beethoven program at the Zurich Tonhalle, I never thought she could pull it off. The original just seemed too iconic and singular to withstand that kind of focus. But to my surprise and pleasure she pulled it off, and then some. Some people noticed the project on line midway through the process and started following along.

Finally, when Jessica Svendsen told me she wanted to create 100 variations of Josef Muller-Brockmann’s classic 1955 poster for a Beethoven program at the Zurich Tonhalle, I never thought she could pull it off. The original just seemed too iconic and singular to withstand that kind of focus. But to my surprise and pleasure she pulled it off, and then some. Some people noticed the project on line midway through the process and started following along. People have asked me many times to say what, exactly, is the point of this project. I’ve always had a fascination with the ways that creative people balance inspiration and discipline in their working lives. It’s easy to be energized when you’re in the grip of a big idea. But what do you do when you don’t have anything to work with? Just stay in bed? Writers have this figured out: it’s amazing how many of them have a rigid routine. John Cheever, for instance, used to wake up every morning in his New York City apartment, put on a jacket and tie, kiss his wife goodbye, and take the elevator down to his apartment building’s basement, when he would sit at a small desk and write until quitting time, at which point he’d go back up. (When it was hot in the basement, he’d strip down to his underwear to work.)The only way to experience this kind of discipline is to subject yourself to it. Every student who has taken this project had a moment where the work turned into a mind-numbing grind. And trust me: it won’t be the first time this happens. The trick is to press on. For each new day (whether it’s Day 28, Day 61, even Day 100) brings with it the hope of inspiration. via http://observersroom.designobserver.com/oblog/entry.html?entry=24678

People have asked me many times to say what, exactly, is the point of this project. I’ve always had a fascination with the ways that creative people balance inspiration and discipline in their working lives. It’s easy to be energized when you’re in the grip of a big idea. But what do you do when you don’t have anything to work with? Just stay in bed? Writers have this figured out: it’s amazing how many of them have a rigid routine. John Cheever, for instance, used to wake up every morning in his New York City apartment, put on a jacket and tie, kiss his wife goodbye, and take the elevator down to his apartment building’s basement, when he would sit at a small desk and write until quitting time, at which point he’d go back up. (When it was hot in the basement, he’d strip down to his underwear to work.)The only way to experience this kind of discipline is to subject yourself to it. Every student who has taken this project had a moment where the work turned into a mind-numbing grind. And trust me: it won’t be the first time this happens. The trick is to press on. For each new day (whether it’s Day 28, Day 61, even Day 100) brings with it the hope of inspiration. via http://observersroom.designobserver.com/oblog/entry.html?entry=24678

Monomyth

courtesy of Stephano:

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see The Hero’s Journey (disambiguation).

Joseph Campbell’s term monomyth, also referred to as the hero’s journey, refers to a basic pattern found in many narratives from around the world. This widely distributed pattern was described by Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949).[1] An enthusiast of novelist James Joyce,[2] Campbell borrowed the term monomyth from Joyce’s Finnegans Wake.[3]

Campbell held that numerous myths from disparate times and regions share fundamental structures and stages, which he summarized in the introduction to The Hero with a Thousand Faces:[4]

| “ | A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man. | ” |

Campbell and other scholars, such as Erich Neumann, describe narratives of Buddha, Moses, and Christ in terms of the monomyth, and Campbell argues that other classic myths from many cultures follow this basic pattern.[5]

A chart outlining the Hero’s Journey.

Copyright © _dreams. All rights reserved.